Kirkus Reviews

THE LOST TRIBE OF CONEY ISLAND: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled Off the Spectacle of the Century by Claire Prentice

This bright story of a shameless huckster evokes a unique bit of Americana at the turn of the 20th century, when the nation dabbled in empire-building and the display of human beings as objects of curiosity was a staple of show business.

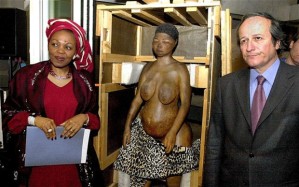

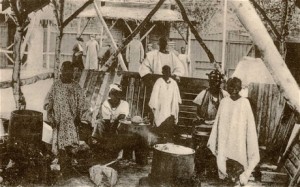

Not long after the United States took control of the Philippines, 50 members of the Igorrote tribe, indigenous to the mountains of Luzon, agreed to travel to America for a year with Dr. Truman Hunt to display salient features of their culture. The happy tribespeople’s native costume was smaller than a stripper’s final revelation, and they excelled in spear chucking and tobacco smoking. On occasion, too, they were headhunters and ready to feast on dogs. Fatherly Dr. Hunt booked his troupe into venues like Luna Park in Coney Island, where they continuously performed in G-strings for gawkers. They ate boiled mongrel until they were quite fed up with their canine diet. Managed by the ever demanding, ever drinking Hunt, the show was a great hit, playing in many cities across the continent. Of course, it was more fakery than ethnography. Journalist Prentice artfully reveals the growing mendacity of the promoter/doctor. The Igorrotes were degraded, robbed of their earnings and held against their will, unable to return home. Throughout their ordeal, the purported savages proved considerably more dignified and civilized than the many showmen charged with their care. In this nicely paced popular history, the author ably develops the diverse ancillary characters, such as the wives of bigamist Hunt, the promoters and the shady lawyers. Eventually, the government pursued the evasive Hunt. The tale ends, improbably, with strange lawsuits. Prentice presents the story of the innocent tribe with sympathy; in her telling, the Igorrotes charm and entertain us once again after more than a century.

The edifying, colorful adventures of headhunters captured in America by a sideshow rascal.

MORE REVIEWS OF The Lost Tribe of Coney Island

“The Lost Tribe of Coney Island is at once an engrossing portrait of the Igorrote people and a fascinating meditation on the dark side of the American Dream. Claire Prentice has a reporter’s nose for a good story, and a novelist’s flair for telling it.” —Karen Abbott, New York Times best-selling author of Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy

“One of those books that is totally unexpected, and delightfully so. An astonishing story, beautifully and compassionately told.” —Alexander McCall Smith, author of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency

“In her rich and absorbing account, Claire Prentice shines a bright light on the ‘primitive’ Igorrotes’ arrival in New York, and one opportunistic man’s quest to profit from a Western obsession with ethnological entertainment. Historically meticulous, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island provides a fascinating glimpse into the heart and soul of America at the turn of the 20th century.” —Gilbert King, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Devil in the Grove

“Combining exhaustive historical research with rich novelistic color, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island thrillingly conjures up two long-vanished and equally exotic worlds. One is that of the ‘savage’ Igorrotes, a tribe of Philippine aborigines known as ‘a peaceful, good-humored, honest, industrious, and likable people,’ apart from their inveterate habit of ‘cutting off the heads of neighboring villagers.’ The other is turn-of-the-century Coney Island, a tawdry, titillating wonderland where respectable city folk flocked to ogle the ‘primitive,’ half-naked residents of the park’s ‘human zoo.’ At the juncture of both looms the larger-than-life figure of Truman Hunt, a quintessentially American huckster in the brazen mold of P.T Barnum. Like visitors to the old Luna Park, readers of Claire Prentice’s page-turning book can expect to be amazed, delighted, and edified.” —Harold Schechter, author of The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, the Model, and the Murder that Shook the Nation

“The Lost Tribe of Coney Island is the fascinating, true-life, more-amazing-than-fiction story of a group of Philippine tribespeople, brought from the Stone Age to the wonders of Coney Island in 1905. Absolutely enthralling.” —Kevin Baker, author of Dreamland and The Big Crowd

“In the annals of exploiting humanity as entertainment, not even Barnum or Ripley can compare to the audacity of Truman Hunt and his eager band of Philippine tribespeople who titillated American audiences in the shadow of Manhattan. Kudos to Claire Prentice for uncovering this overlooked bit of history and bringing it to life as a thoughtful page turner. Packed with a ridiculously robust cast of lively characters, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island manages to explore imperialism, sensationalism, greed, fame, and deceit, deftly capping it all off with a manhunt. Obsessively researched and written with vigor and compassion, the story of America’s taste for the exotic and illicit raises uneasy questions about who’s civilized and who’s savage.” —Neal Thompson, author of A Curious Man: The Strange & Brilliant Life of Robert ‘Believe It or Not’ Ripley

“The author tells a riveting tale of the American dream gone wrong . . . Without scholarly pretensions, Prentice has crafted an entertaining popular account likely to appeal to fans of true crime and social history.” Library Journal

You must be logged in to post a comment.