23 May 2016

How one man saved a generation of premature babies

AP

For years doctors in the US made little attempt to save the lives of premature babies, but there was one place distressed parents could turn for help – a sideshow on Coney Island. Here one man saved thousands of lives, writes Claire Prentice, and eventually changed the course of American medical science.

In the early years of the 20th Century, visitors to Coney Island could see some extraordinary attractions. A tribe transported from the Philippines, “midget villages”, a re-enactment of the Boer War by 1,000 soldiers including veterans from both sides, and death-defying roller coaster rides. But for 40 years, from 1903 to 1943, America’s premier amusement park was also home to a genuine life-and-death struggle, played out beside the surf.

Martin Couney’s Infant Incubator facility was one of Coney Island’s most popular exhibits. “All the World Loves a Baby” read a sign above the entrance. Inside, premature babies fought for their lives, tended by a team of dedicated medical staff. To see the babies, you paid 25 cents. A guard-rail prevented visitors getting too close to the tiny figures encased in incubators.

Why were premature babies, who would now be cared for in a neonatal ward, displayed as entertainment?

Image copyright Beth Allen

The man who ran the exhibit was Martin Couney, dubbed “the incubator doctor” – and although he practised in the sideshows, his operation was cutting-edge.

Couney employed a team of nurses and wet nurses who lived onsite, along with two local physicians.

In America, many doctors at the time held the view that premature babies were genetically inferior “weaklings” whose fate was a matter for God. Without intervention, the vast majority of infants born prematurely were destined to die.

Couney was an unlikely medical pioneer. He wasn’t a professor at a great university or a surgeon at a teaching hospital. He was a German-Jewish immigrant, shunned by the medical establishment, and condemned by many as a self-publicist and charlatan.

But to the parents of the children he saved, and to the millions of people who flocked to see his show, he was a miracle-worker.

Image copyright Beth Allen

The incubators Couney used were the latest models, imported directly from Europe – France was then the world leader in premature infant care with the US lagging several decades behind.

Each incubator was more than 5ft (1.5m) tall, made of steel and glass, and stood on legs. A water boiler on the outside supplied hot water to a pipe running underneath a bed of fine mesh on which the baby slept, while a thermostat regulated the temperature. Another pipe carried fresh air from outside the building into the incubator, first passing through absorbent wool suspended in antiseptic or medicated water, then through dry wool, to filter out impurities. On top, a chimney-like device with a revolving fan blew the exhausted air upwards and out of the incubators.

Caring for premature babies was expensive. In 1903, it cost about $15 a day ($405 or £277 today) to care for each baby in Couney’s facility.

But Couney did not charge the parents a penny for their medical care – the public paid. They came in such numbers that Couney easily covered his operating costs, paid his staff a good wage and had enough left over to begin planning more exhibits. In time, these made Couney a wealthy man.

Image copyright AFP

Beth Allen: “Nobody else was offering to do anything to save me”

Beth Allen held by one of the incubator nurses. Image copyright Beth Allen

Couney saw his job as not only to save the lives of the premature babies, but also to advocate on their behalf. He gave lectures reciting the names of famous men who had been born prematurely and gone on to achieve great things, such as Mark Twain, Napoleon, Victor Hugo, Charles Darwin, and Sir Isaac Newton.

He maintained his facility for 40 years at Coney Island, and set up a similar one at Atlantic City in 1905, which he also ran until 1943. Over the years he took his show to other amusement parks, and to World’s Fairs and Expositions across America.

Although he made his name and his fortune in America, it was in Europe that Couney got his first taste of life as a showman. In 1897 he exhibited incubators at the Victorian Era Exhibition in Earls Court and they were a huge hit. Some 3,600 people visited the show on opening day alone, and the British medical journal, The Lancet, gave it a glowing write-up.

The following year, Couney made his American debut at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska. Sensing the huge opportunities for someone like him to exhibit in America, where there was always a fair or an expo taking place somewhere, Couney immigrated.

From 1903, Coney Island was his main base but he travelled around the country as work demanded.

Martin Couney 1869-1950

Image copyright New York Public Library

- 1869 Martin Couney is born in Krotoschen, then part of Prussia

- 1903 Couney marries one of his nurses, Annabelle Segner, in New York

- 1907 His wife gives birth to a daughter, Hildegarde, born six weeks premature, weighing just 3lb – Hildegarde later trained as a nurse and joined her father’s business

- 1950 Couney dies at the age of 80. His death is marked with an obituary in the New York Times

Couney’s techniques were advanced for the time, including his emphasis on breast milk and his strictness about hygiene. But some of his methods were unconventional. Most hospital doctors believed that contact with premature babies should be kept to a minimum to reduce the risk of infection. But Couney encouraged his nurses to take the babies out of the incubators to hug and kiss them, believing they responded to affection.

Eager to distance himself from Coney Island’s more freakish elements, Couney stressed that his facility was a miniature hospital, not a sideshow attraction. The nurses wore starched white uniforms. He and the doctors wore suits topped with physician’s white coats.

The incubator facility was always scrubbed spotlessly clean. Couney employed a cook to prepare nutritious meals for his wet nurses. If any were discovered smoking, drinking alcohol or snacking on a hot dog, he would fire them immediately.

Image copyright Beth Allen

Yet Couney was not averse to adopting a few showman’s tactics himself. He instructed the nurses to dress the babies in clothes several sizes too large to emphasize how small they were. A big bow tied around the middle of their swaddling clothes further added to the effect.

Despite his life-saving work, children’s charities, physicians and health officials accused the incubator doctor of exploiting the babies and endangering their lives by putting them on show. There were regular attempts to shut him down.

Luna Park, Coney Island, New York, 1890. Image copyright Google

But as time passed, Couney’s track record of saving lives, and his evident sincerity, began to attract supporters from the world of mainstream medicine. In 1914, while exhibiting in Chicago, Couney met a local paediatrician, Julius Hess, who would go on to become known as the father of American neonatology. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship and an important professional relationship. The two men ran an infant incubator facility together at the 1933/34 Chicago World’s Fair.

Some physicians began sending babies to Couney, a tacit acknowledgement at last of the quality of care the babies received in his facility.

In a career spanning nearly half a century he claimed to have saved nearly 6,500 babies with a success rate of 85%.

“Martin Couney was an incredible man – he should be famous for what he did.” Carol Boyce Heinisch, Incubator baby, born 1942

Hospitals in the US were slow to establish their own dedicated facilities for premature babies, though. The first on the Eastern seaboard arrived in New York in 1939, 36 years after Couney brought his show to Coney Island.

In an article reflecting on Couney’s long career in the New Yorker in 1939, the legendary journalist A J Liebling noted: “There are not enough doctors and nurses experienced in this field to go around. Care of prematures as private patients is hideously expensive… six dollars a day for mother’s milk… rental of an incubator and hospital room, oxygen, several visits a day by a physician, and fifteen dollars a day for three shifts of nurses.”

The best medical minds in New York couldn’t come up with a workable model to save these vulnerable babies. Yet, 40 years earlier, a young immigrant from Europe with little in the way of experience had done just that.

Today Couney’s legacy is being re-examined by doctors, and many of Couney’s “babies” speak proudly in his defence.

Carol Boyce Heinisch was born prematurely in 1942 and taken to Couney’s exhibit in Atlantic City, New Jersey. “Martin Couney was an incredible man. He should be famous for what he did. He saved thousands of us,” she says. She still has the identity necklace made of pink beads, with her name in white beads, which she was given in the incubator facility.

Hildegarde Couney holds the baby Carol Boyce Heinisch. Image copyright Carol Boyce Heinisch

“Nobody else was offering to do anything to save me,” says another of the babies, Beth Allen, who was born three months premature in Brooklyn in 1941. When a physician suggested her parents take her to Coney Island, her mother refused, insisting her daughter wasn’t “a freak”. Couney came to the hospital and persuaded her parents to let him care for her. Every Father’s Day, her parents took her to see Couney. When he died, in 1950, they attended his funeral. “Without Martin Couney I wouldn’t have had a life,” she says.

Today it would be considered unethical to exhibit premature babies and charge fairgoers to see them, notes Dr Richard Schanler, director of Neonatal Services at Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York and Northwell Health. “But you have to think back to that time,” he says.

“Nowadays when new technology comes out we do randomised controlled trials. They didn’t do those back then so the shows were a way of demonstrating the benefit of using incubators… We owe a lot to Couney and the work he was doing.”

![]()

Bizarre tale of the Boardwalk babies: How thousands of premature infants were saved from certain death by being part of a Coney Island entertainment sideshow

- Physician Martin Couney held a sideshow that featured the tiny babies

- The Coney Island facility ran from 1903 to 1943

- Punters would pay 25 cents to look at the babies – funding their care

- Couney was shunned by the medical world for being a tasteless showman

- But he claimed to have saved a total of 6,500 premature babies

- The baby incubators feature as an attraction in HBO’s Boardwalk Empire

By Alexandra Genova For Dailymail.com and Claire Prentice

A midget city, a wild animal show and a bearded lady were all attractions at New York’s most insalubrious entertainment park.

But few will be aware of one man’s sideshow that not only entertained but saved the lives of thousands of premature babies.

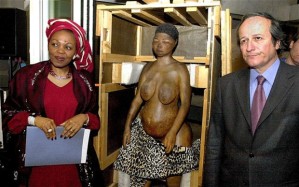

Martin Couney, dubbed ‘the incubator doctor’ (pictured with a pair of premature babies) held a stall that displayed a genuine life and death struggle – and proved to be one of Coney Island’s most popular attractions

Behind the gaudy facade, premature babies were fighting for their lives, attended by a team of medical professionals (pictured are two of Couney’s nurse with premature babies)

Shocking as it may seem now, physician Martin Couney, dubbed ‘the incubator doctor’, held a stall that displayed a genuine life and death struggle – and proved to be the one of the Island’s most popular attractions.

It also changed the course of American medical science.

At the time premature babies were considered genetically inferior, and were simply left to fend for themselves and ultimately die.

Couney offered desperate parents a pioneering solution that was as expensive as it was experimental – and came up with the very unusual way of covering the costs.

For 40 years, from 1903 to 1943, the Jewish-German physician held an infant incubator facility at the amusement park dubbed ‘All the World Loves a Baby’.

But behind the gaudy facade, premature babies were fighting for their lives, attended by a team of medical professionals. To see them, punters paid 25 cents.

The public funding – albeit via a crude transaction – paid for the expensive care, which cost about $15 a day in 1903 (the equivalent of $405 today) per incubator.

The incubators themselves were a medical miracle, 40 years ahead of what was being developed in America at that time.

Each incubator was made of steel and glass and stood on legs, about 5ft tall. A water boiler on the outside supplied hot water to a pipe running underneath a bed of mesh, upon which the baby slept.

One such baby was Beth Allen (pictured) who was born three months premature in Brooklyn in 1941

The incubators (pictured) themselves were a medical miracle, 40 years ahead of what was being developed in America at that time

For 40 years, from 1903 to 1943, the Jewish-German physician held an infant incubator facility at the amusement park dubbed ‘All the World Loves a Baby’ (pictured)

Couney’s nurses all wore starched white uniforms and the facility was always spotlessly clean. An early advocate of breast feeding, if he caught his wet nurses smoking or drinking they were sacked on the spot

A thermostat regulated the temperature and another pipe carried fresh air from the outside of the building into the glass box, that first passed through absorbent wool suspended in antiseptic or medicated water, then through dry wool, to filter out impurities.

While on top, a chimney-like device with a revolving fan blew the exhausted air upwards and out of the incubators.

Couney, who had been shunned by the medical world as a tasteless showman told interviewers he would give up his carnival display when there were decent medical alternatives.

At the time, American doctors mostly viewed premature babies as ‘genetically inferior’.

This meant that without intervention, the vast majority of babies were likely to die.

Having traveled over from Europe, following several prominent exhibitions, including the 1897 Victorian Era Exhibition in Earls Court, Couney made his name in America.

As well as a facility in Atlanta, he also toured the country giving lectures about his work. He recited the names of notable figures born prematurely who had gone on to do great things.

Among those were Charles Darwin, Sir Isaac Newton, Napoleon, Victor Hugo and Mark Twain.

Though the stall sat side by side with ‘freak show’ attractions, Couney ran a professional set up.

Allen said: ‘Without Martin Couney I wouldn’t have had a life.’

The baby incubators were incorporated into the HBO show Boardwalk Empire, which was set on the Atlantic City Boardwalk as opposed to Coney Island.

His nurses all wore starched white uniforms and the facility was always spotlessly clean.

An early advocate of breast feeding, if he caught his wet nurses smoking or drinking they were sacked on the spot. He even employed a cook to make healthy meals for them.

In a career spanning nearly half a century he claimed to have saved nearly 6,500 babies with a success rate of 85 per cent, according to the Coney Island History Project.

One such baby was Beth Allen, who was born three months premature in Brooklyn in 1941.

Though her parents initially refused to take their baby there despite their physician’s suggestion, Couney came down to the hospital and persuaded them.

Allen told the BBC that they eventually agreed, and every year since her parents took her to see Couney on Father’s Day in gratitude. When he died in 1950, they attended his funeral.

Claire Prentice has made a BBC Radio Documentary, Life Under Glass, and is the author of Miracle at Coney Island.

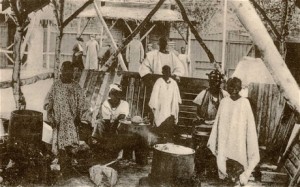

Spectacular: The Igorrotes lived a ‘village’ in the middle of Luna Park, Coney Island, as visitors gaped at the ‘savages’ in open-mouthed wonder

Spectacular: The Igorrotes lived a ‘village’ in the middle of Luna Park, Coney Island, as visitors gaped at the ‘savages’ in open-mouthed wonder Exciting: Visitors were invited to get up as close to the fearsome, head hunting warriors as they dared

Exciting: Visitors were invited to get up as close to the fearsome, head hunting warriors as they dared Conman: Dr Truman Hunt brought the show to America. Later, when he began to take the villagers around the country, he stole what was owed them and treated them shamefully. He was eventually arrested by Pinkertons

Conman: Dr Truman Hunt brought the show to America. Later, when he began to take the villagers around the country, he stole what was owed them and treated them shamefully. He was eventually arrested by Pinkertons  Trapped: In the Philippines, the tribespeople were accustomed to roaming free in the Northern Luzon wilds; at Coney Island they were forbidden from leaving their enclosure

Trapped: In the Philippines, the tribespeople were accustomed to roaming free in the Northern Luzon wilds; at Coney Island they were forbidden from leaving their enclosure Exotic: The Igorrotes, with their keen sense of humor, near nudity, head hunting and dog eating, quickly captured the imagination of the earliest American visitors to the Philippines

Exotic: The Igorrotes, with their keen sense of humor, near nudity, head hunting and dog eating, quickly captured the imagination of the earliest American visitors to the Philippines Trapped: In the Philippines, the tribespeople were accustomed to roaming free in the Northern Luzon wilds; at Coney they were forbidden from leaving their enclosure

Trapped: In the Philippines, the tribespeople were accustomed to roaming free in the Northern Luzon wilds; at Coney they were forbidden from leaving their enclosure

Forgotten: The shameful episode, despite being so spectacular at the time, has faded from public memory

Forgotten: The shameful episode, despite being so spectacular at the time, has faded from public memory

You must be logged in to post a comment.